Saturday, December 13, 2008

Friday, December 12, 2008

SCORCHED EARTH AND CONCENTRATION CAMPS - Killings of almost genocidal proportions.

My mother and her sister. Imprisoned as young children, in the Johannesburg Fort.

[PLEASE NOTE:When this blog was first published, I sincerely believed that Queen Elizabeth11 had made a full, formal apology to the people of South Africa in 1999. However, it now appears that I was sadly mistaken, and I am indebted to the many readers who have sent me links to reliable sources, disproving my statements. All point to the fact that she made some vague apology but stopped short of actually apologizing for the concentration camps. An example, from The World Today Archive - Thursday, 11 November, 1999: Reporter Ben Wilson quotes JOHN HIGHFIELD: .....”Queen Elizabeth has stopped short of saying sorry for the death and hurt caused to the Afrikaners in the Anglo-Boer war.” http://www.abc.net.au/worldtoday/stories/s65787.htm, and Marcelle L writes: “So it seems she did but she didn't.”]

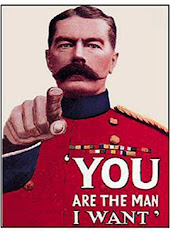

Even more tragic than a war waged against a people whose only transgression was the fact that gold had been discovered in their small republic, was the cruel condemnation of its people and the total ignorance of the causes. The fire was fuelled by the media of the day - together with individuals who then (as many still are) were ignorant of the true circumstances which led up to what I can now only describe as a holocaust. In the days when 'the sun never set on the British Empire' it stands to reason that propaganda aimed at whipping up 'patriotism' succeeded in every part of that Empire - from Australia to Canada - and it was not long before men were marching, bands playing, and women waving banners as their menfolk answered the call to go and 'deal with those Boers!'

No war is ever fought without loss of life, but the greatest tragedy of the Second Boer War (1900-1902) was the internment of women and children in concentration camps, which led to massive loss of life. Approximately 25 percent of the interned died, including 50 percent (or half) of the children. In addition, 30,000 farmhouses and 21 villages were destroyed. Among the burgers (or Boers) 3,990 were killed and 1,081 died of disease or accidents in the veld. If these figures are measured against the total number of Boers, and as the entire Boer population in both republics was just over 200,000, the mortality rate meant that nearly 15 percent of the entire Boer population was wiped out!. That is why it is safe to declare that the death rate was indeed of 'genocidal proportions'.

Twelve percent of the Boer deaths were battle related; six percent died from other causes while on commando; 17 percent were adults in the camps, and 65 percent were children under the age of 16 years. To put this in perspective, among the 27,927 Boers who died in the camps, 4177 were adult women, and 22,074 were children under the age of 16. It was nothing short of diabolical that by October 1901, the number of inmates in the 45 camps had increased to 118,000 Whites and 43, 000 non-Whites. The death rate was 344 per thousand amongst the Whites and at one stage, in the Kroonstad camp, the death rate was 878 per thousand.. - Among them were people from whom I am descended.

I never knew my grandmother or my great-grandmother. As I have written in my profile, the latter died in one of the British concentration camps, and, in that same camp, my grandmother's health was compromised to the extent that she lived for only five years after having been freed. She was only thirty-three at the time of her death.

* * * * * * * *

Actually, from the time my forebears - Dutch and French - had come to South Africa, they, especially the French, had never really had an easy time of it. Granted the Dutch had not been forced to flee their homeland as the French Huguenots were driven to do, but the mandate they had been given was pretty stiff...

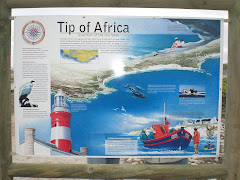

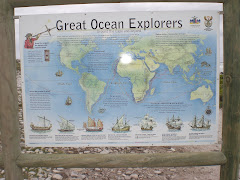

It had all started with the wreck, in 1647, of a Dutch East India Company ship called the Haarlem, which was destined to play a profound part in the history of South Africa. While not anticipating a good outcome to a rescue mission, another ship — with a young ships-surgeon by the name of JAN VAN RIEBEECK, on board — was sent to try and find survivors.

Surprising evidence of the ability of the shipwrecked Dutch sailors to survive there, now seemed to suggest that the place was habitable; and, if fresh supplies could there be made available to vessels en route to the Far East, and back, it was possible that the curse of the dread disease, Scurvy, could be held at bay. Within four years, in 1651, the Chamber of XVII in Amsterdam was ordering that the ships, the Dromedaris, the Goede Hoop and the Reiger be fitted out for the proposed journey to the Cape of Good Hope.

So it happened that the first major, permanent White settlement in Africa came about in 1652, when a Dutch trading company known as the Dutch East India Company sent one of its officials, (Jan van Riebeeck), to what is now called Cape Town, where he was to build a re-supply station for company ships traveling to and from Asia. It was thus the Dutch who realized the strategic and economic importance of the Cape and that is how it came about that, acting on a commission from the Dutch-East India Trading Company, Jan van Riebeeck anchored in what is now known as Table Bay at the foot of the Table Mountain on April 6, 1652. Ironically, although the Dutch never intended to establish a proper colony, and it was only to be a re-supply facility, it was around this station that the first White settlement spread. It was where they met the first non-Whites — tribes of Hottentots and Bushmen who were happy to trade cattle with the new settlers.

In commissioning Jan Anthoniszoon van Riebeeck to establish the proposed refreshment station, the Dutch East India Company had made a wise choice. After joining the organization as an assistant surgeon, he had, in April 1639, sailed to Batavia (now Jakarta). From there he had gone to Japan, and in 1645 had taken charge of the company trading station at Tongking (Tonkin; now in Vietnam) and they had at their disposal a man accustomed to living in foreign places, who was both a physician and a merchant. He was a man eminently suitable for the task ahead.

History makes it clear, however, that life was not always easy, and also that there were no black people at the Cape at that time. Late in 1652, Jan van Riebeeck and his companions had been instructed to establish a strong base to provide the Company’s ships with fresh groceries - mainly meat and vegetables - on the long journey from Europe to Asia, and it had also soon become obvious that a fort would have to be built but, after his first winter at the Cape, when twenty of the eighty-two men and eight women who had accompanied him, died, he realized that the task of maintaining the refreshment station was too formidable for the remnant to carry out. Slaves were thus brought to help; many of them politically banned people imported from Java and Sumatra.

The Landing at the Cape

Because the ‘European’ settlement in South Africa started in Cape Town, it is called the ‘Mother City’ to this day. As has already been said, the Dutch East India Company had originally intended only to establish a refreshment station for the benefit of the crews of their merchant ships, en route to India, and back — until, Maria, wife of the first commander, Jan van Riebeeck, bore a child there; and subsequent births among other families wrought the desire for a more permanent state of affairs. The people longed to be able to put down roots; to be 'settled' there and not merely ‘stationed’. Thus, in time, the ‘refreshment station’ would become a settlement, the settlement a colony, and those who had left the service of the Company to farm on their own, would be known as 'Free Burghers’.

During the regime of an excellent Governor, Simon van der Stel, the colony spread north and east and flourished. In succeeding him, however, his greedy son did not exhibit any of the traits which had made Simon a good governor. Personal avarice moved Willem Adriaan to much treachery; not least among his wrongdoings, neglect of his official duties and the obsession with his own extensive estates.

Among other things, he dealt the young agricultural industry a crushing blow by proclaiming that no Free Burgher could trade with passing vessels until he and his cronies had been given the opportunity to sell their own produce. Before long, the colonists were desperate to be rid of the young tyrant.

I take the liberty of quoting here from my book, Storm Water:

“Driven by desperation, man called Henning Huising, aided by another burgher by the name of Adam Tas, took the lead in drawing up two petitions, which were sent to Holland and Batavia, but it was not long before the Free-Burghers were taken into custody and tried before an irregular court, in an attempt to induce them to withdraw their signatures. Many who did so, were still not freed, but were left to languish in the dungeons of the Castle. Huising and three other men were deported.

“It was not long before they were made aware of the counter-petition which Governor Willem Adriaan had been preparing, and received the news that Van der Stel had dispatched his document with the fleet which had sailed on the previous day, knowing that the burghers had sent their latest petition to Holland by the same ship."

If I might be permitted to use another quote: "The speaker then went on to list how the Governor utilized materials, officials, gardeners and slaves of the Company to work the farm of which he had become the owner by dishonest means; how he neglected his official duties because of the weeks he spent on this farm while he was reported to be about his business at the Castle.

"Presently he referred to the regulation of 1688, which prohibited officials of the Company from farming. Van der Stel had not long abided by this – he was saying – because, but seventeen years later, the Governor and his friends were already in a position to supply the greatest part of the Company’s requirements in corn, wine and meat.

"There was a dramatic pause during which the man shrugged his shoulders eloquently. Originally it had not been so serious, he continued in a monotonous, plaintive voice, because the Company only received these supplies through the middleman, or contractor, who held the monopoly to supply the refreshment station with such things. Speedily, however, the Governor had taken the obvious step which gave him control of the contractors, so that they would be obliged to purchase, first, the produce of his farm and that of his friends.

....."An atmosphere of suspense hung over the entire settlement. Wherever people went, it seemed, the chief subjects of discussion were inevitably the two conflicting documents which were travelling simultaneously to Europe.

“What incenses me,” Paul Roux said as they sat down to dinner,” is that so many people were forced to sign the Governor’s damnable counter petition. Heaven only knows how many unsuspecting people were prevailed upon to add their signatures at the banquet, and it would not surprise me in the least to learn that there are many additional names which appear on the document without the knowledge or permission of the people concerned!”

And again from the book, the happy outcome:

“Our petition was originally given to a man by the name of Bogaert – as you no doubt recall, Madame la Comtesse – who was to have carried it to Holland for us,” Barend explained, almost breathless with suppressed excitement. “But when - fortuitously - he chanced to encounter the banished Huising on the same ship, he handed the document to him. Henning Huising was then able to lay it personally before the Council of Seventeen – who better to do so? – and took the opportunity of pleading our cause at the same time. That is, of course, the reason for the unprecedented victory we have attained over the tyrants. If Willem Adriaan had only known! When, having banished him, he sent Huising home by the same fleet as our petition, he had already, metaphorically, cut his own throat!”

ARRIVAL OF THE FRENCH

They prospered, those early Dutch settlers, to be joined in time by the French, who brought with them the cuttings for planting vineyards from which a vast winemaking industry would develop and become famous all over the world. The Dutch welcomed immigration, but behind the arrival of the new colonists lay one of the most tragic stories of religious persecution in history.

Wednesday, December 10, 2008

Where do I begin?

According to the Passenger list of the BERG CHINA, which sailed from Rotterdam in Holland on 20 March 1688, my first French ancestors arrived in Table Bay, South Africa, on 4 August 1688. Huguenot, or French Protestants - members of the Reformed Church which had been established in 1550 by John Calvin – the husband is reputed to have carried with him a Bible hidden in a loaf of bread.

According to the Passenger list of the BERG CHINA, which sailed from Rotterdam in Holland on 20 March 1688, my first French ancestors arrived in Table Bay, South Africa, on 4 August 1688. Huguenot, or French Protestants - members of the Reformed Church which had been established in 1550 by John Calvin – the husband is reputed to have carried with him a Bible hidden in a loaf of bread. Individual Huguenots had settled at the Cape of Good Hope from as early as 1671, but after a commissioner had been sent out from the Cape Colony in 1685 to attract further settlers, an organized, large-scale emigration of Huguenots to the Cape of Good Hope took place during 1688 and 1689, among them, as already mentioned, my mother’s ancestors from La Motte d'Aigues in Provence, fleeing from their country after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes.

This was a law promulgated by Henry IV of France in 1598, granting religious liberty and full civil rights to the Protestant Huguenots, but the revocation of the edict by Henry’s grandson, Louis XIV, in October 1685, brought an end to that freedom, declaring Protestantism illegal in terms of a new law. The persecution that ensued was nothing short of horrendous, and as the penalty often included burning at the stake, it was small wonder that the Huguenots were eager to take advantage of the invitation to emigrate to the Cape of Good Hope. - Le Cap de Bonne-Espérance. - The name alone must have spelled hope to them.

No existing document paints a more vivid picture of the suffering the Huguenots had to endure before fleeing their homeland, than the leaflet that came with a Huguenot Cross given to me by a friend. As the leaflet was creased, torn, and had been badly photocopied,it was difficult to patch together, and I am indebted to my son for helping me to fill in the gaps.

THE STORY OF THE HUGUENOT CROSS.

Over the years there has been much speculation, and many different stories have been exchanged about the origins of the Huguenot Cross. However,the consensus seems to be that it was worn for the first time in the Cevennes. — As the pamphlet suggests, it was a cross that 'evolved through tragic circumstances!'

During the persecution of the Huguenots, their religious gatherings had perforce to be kept secret. They were usually held in caves and other clandestine places, and directed by one of the members. In the case of weddings and christenings they had to wait until a preacher was in the neighbourhood.

We learn that one day, somewhere in the Cevennes, a group of Huguenots had gathered, and the preacher was already engaged in marrying four young couples when the dreaded French Dragoons appeared on the scene. Many of the Huguenots succeeded in escaping, but two of the bridal couples were apprehended. In the nearest town they were given the choice: “Become Roman Catholics or die at the stake!” but, undaunted, they refused to recant their Huguenot convictions.

What I find most appalling is that the piles of wood prepared on the market square for the burning of the youthful couples, were arranged in such a way that the condemned could watch each other burn to death; however, betraying no fear, the four doomed young people sang while they were brought closer and bound, each to a stake.

It is said that their psalms rose to heaven along with the flames, until their voices faded into silence.

Suddenly, from the crowd, a woman's voice called out: “I see the flames rise to heaven. They unite in a mighty dome of fire, and in the centre it shoots its rays to the North, the South, the East and the West — the Morning Star! The sign of our Master, Jesus Christ! Praise the Lord! He is with us to the end!”

A metal worker from Nimes, who saw and heard everything the woman had said, subsequently made a kind of medallion, approximately the size of a five-cent piece. "The nucleus resembled the Maltese cross (the symbol of the Crusaders) and the four arms of the cross were linked with a smaller circle’, which refers to the flames that united them. The space between the arms was fashioned in the shape of a heart. The four hearts are to remind us of the love of the two young couples who, remaining steadfastly true to their faith, were burnt at the stake on their wedding day."

This Medallion was afterwards adopted by the Huguenots as their symbol.

In time to come the cross was not only made from iron, but also from silver, and even gold. The dove was added to represent the Holy Ghost. After the dreadful persecutions following the revocation of the Edict of Nantes, it was replaced with a pearl, symbolizing a tear. My own cross still has the dove.

The Huguenot cross is a symbol of steadfast conviction — a faith so strong that it did not even fear the stake. Descendants of the Huguenots are not allowed to forget their origins, nor to consider their religious precepts merely superficial.

St. Bartholomew's Day.

What has been described as one of the most horrifying holocausts in history - the infamous St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre - took place on August 24, 1572 when, beginning in Paris, French soldiers and members of the Roman Catholic clergy fell upon the unarmed Huguenots. It is said that blood ‘flowed like a river’ throughout the entire country, and an estimated 100,100 Protestant men, women and children were killed. Soon, we are told, the rivers of France were filled with so many corpses that, for many months, the fish were inedible. It is ghastly to picture that wolves fed upon the decaying bodies.

Now in referring to the Boer War as a holocaust, it makes me cringe to realize that that this was not the first associated with my French ancestors. How cruel it seems that, after making it to their haven of "Good Hope" after one holocaust, many of their descendants would suffer and die in another!

* * * * *

The settlement evolves...

The Dutch East India Company encouraged the Huguenots to immigrate to the Cape because they shared the same religious beliefs, and also because most of them were highly trained craftsmen or experienced farmers, specifically in viticulture and oenology (the growing of grapes and making of wine, brandy and vinegar). They, as well as their descendants, proved that they were hard-working and industrious, and their efforts led to a marked increase in the improvement of quality Cape wines. A number of wine estates have French names to this day, as a reminder of their important contribution to this industry in the Western Cape. Three years after the arrival of Jan van Riebeeck at the Cape, the number of vine plants had increased from 100 in 1655, to 1.5 million in 1700.

Feathers were well and truly ruffled, however, when Paul Roux, the school master and ‘sieketrooster’ (comforter of the sick) who had arrived on the same ship as the first French members of my family, was commanded by the Dutch East India Company’s Council of Seventeen to use only Hollands as the medium of instruction in his school. I borrow once more from my book, Storm Water , as Count Louis de Maupassant, in conversation with Roux, protests:

"Integrate? – Why, we don’t even speak the same language – except when it becomes absolutely necessary … in discussion with our neighbours, perhaps!” He knocked his pipe out violently against the fireplace. “What you have just said is perfectly true – it does happen – but is that a good reason why we should allow it to happen to us? … No, my dear friend, that is the same reasoning as to say: ‘We all have to die one day – why not just take poison now and be done with it!’”

The schoolmaster still smiled his patient smile. “Even the Dutch are not speaking the same language any more, mon ami. The years have made a great difference to us all. The other day I heard a newly-arrived official complain to a colleague that he could barely understand what the Dutch colonists were saying! He described their conversation as ‘Kaaps-Hollands’¨ – Cape Dutch! Some of our French words have crept into their Mother tongue, and some of theirs into ours. A new generation of children have already incorporated a few Malay expressions – and even a Hottentot* sound or two!"

(*The Khoikhoi, also called 'Hottentots'.)

From this, over the centuries, came the language which is now known as 'Afrikaans'.

* * * * * *

How the Napoleonic Wars affected the Cape Colony

Disregarding the fact that it was the Dutch who had established the colony and that it was 'owned' by the Dutch East India Company, the first British occupation of the Cape began on 16 September 1795 when the Prince of Orange acquiesced to British occupation and control of the Cape Colony, and, by the time it ended in March 1803, the Dutch had lost their citizenship, and British immigrants seeking a better life in the 'colonies' had also begun to arrive.

In March 1802, peace was made between France and Britain, and, as part of the peace agreement, Britain promised to give the Cape back to the Batavian Republic. (Yet another new name given to the Netherlands.) A year later, Major-General Dundas and the British troops left the Cape, but events in Europe would all too soon cause Britain to take over the administration of the Cape once more because of its importance to ships trading with India.

When the war between Britain and France began again in 1803, Britain was once more concerned about the possibility that France might take over the Cape, as a result of which a large British fleet arrived at the Cape in January 1806, and soon defeated the Dutch troops. Again no changes were made in the way that the Cape was governed, except that it was no longer ruled by a Company but by a Governor appointed by the British Government, and the burghers at the Cape were allowed to trade more freely than they had been able to before.

The second occupation started in January 1806, and South Africa remained a British colony until 31 May 1910 - when it became the Union of South Africa. Bound to France by an alliance set up by its government in 1798, the Netherlands had meanwhile been renamed the Batavian Commonwealth by Napoleon, with executive power placed in the hands of a dictator in 1805. A year later, in 1806, that name was replaced by ‘the Kingdom of Holland’, under the rule of Napoleon’s brother, Louis Bonaparte, and incorporated into the French empire in 1810.

While the original settlers had come mainly from the Netherlands and Friesland, their numbers had been swelled by French and German religious refugees, and by then they had integrated, to become Afrikaners. The full details of the gradual but steadily mounting fermentation of dissatisfaction among the Afrikaners under British rule are too many and varied to included here, but there was, for example, the disadvantage of not being provided an interpreter, if and when they were required to appear in court.

By the beginning of the 19th century many of the settlers had begun to move eastward. Early marriage was the norm, and this, in turn, had brought about a significant rise in the size of the population, triggering concern among the elders that, if they did not prepare for the future, there would be no land for their children to inherit. … A pressing problem at a time when land prices had risen.

In their new environment they had very soon found themselves embroiled in border wars with the Xhosa, while the government did not have the money to protect them. To make matters worse, they were never reimbursed for damages when, having been sent on expeditions for the government, they had used their own horses and equipment. Not unlike the situation in the covered wagon days in what is now the United States of America, it eventually seemed to them that there was no alternative but to prepare their wagons, inspan the oxen, and set off into the great unknown.

Thursday, November 27, 2008

THE GREAT TREK

It's not so bad when you're on level ground,but crossing the Drakensberg is another matter altogether; especially when you strike a snag, thousand of miles away from home!

‘Voortrekker’ is an Afrikaans word which literally means ‘one who moves ahead’ or ‘first-forward traveller.’ They were the people of Dutch, German and French origin who ventured into the unknown, under different leaders, in what is called the Great Trek, to get away from the British-controlled Cape Colony. In a recently-written history of my ancestors, I wrote that 'after fleeing to avoid being burnt at the stake, and further risking risking their lives to get to Holland and the ship which would take them to South Africa, their descendants found no peace in the Cape, and in the North they faced the Boer War.’ It breaks my heart to have to add that "Today History is tragically repeating itself in South Africa as their present-day descendants move away in their thousands, seeking peace and security for their families in other lands!"

The reasons for ‘trekking’ from the Cape, were many and varied – among them the fact that the Afrikaans-speaking burghers were not provided with interpreters when, and if, they had to appear in court, and that, with the passage of time, British control at the Cape became more rigid, depriving the farmers of participation in local government. As they thus had no say in the running of the colony, the people began to move eastward, where they had their first encounter with the Xhosa, only to discover that the government did not have the money to protect them during the border wars which ensued. To make matters worse this, in turn, caused fear and frustration among the frontier community who, already suffering heavy losses of lives and livestock, were required to go on expeditions for the government with no hope of remuneration when their own horses and equipment suffered danger.

Another reason for discontent arose because ownership of their own land was paramount with these people. They traditionally married early in life, rapidly increasing the population, and soon realized that where they had established themselves there would be no land for their children to inherit. It was of great concern to them when - while they were already dealing with a drought in the 1820s and 1830s - land prices rose, farmland became limited as a result of the constant fighting, and the farmers found it more and more difficult to make a living. It became clear that there wasn't enough grazing for both Xhosa and Dutch stock farmers.

Tuesday, November 25, 2008

THE FIRST BOER WAR and a family hero.

The purpose of this blog is not to dwell on the trek itself. It would take a very thick book to describe in detail, the many tribulations – including the massacre of one party - the Boer farmers endured as they braved the unknown to travel, first east along the coast away from the Cape towards Natal, and thereafter north towards the interior, eventually establishing the republics that came to be known as Orange Free State and the Transvaal (literally meaning 'across/beyond the Vaal River', a tributary of the Orange River). How can one, for instance, even begin to imagine how those who went to what is now known as Natal, managed to take their wagons to pieces in order to cross the formidable Drakensberg Mountains.

The British had not tried to stop the trekkers from moving away from the Cape, and it transpired that they were not the only ones searching for pastures new... As the Boers were opening up the interior for those who followed, the British were gradually extending their control away from the Cape, along the coast to the east, eventually annexing Natal in 1845. They, the British, subsequently ratified the two new Boer Republics in two treaties: the Sand River Convention of 1852 which recognized the independence of the Transvaal Republic, and the Bloemfontein Convention of 1854 which recognized the independence of the Orange Free State. Transvaal Voortrekker representatives and commissioners of the British Government attended the convention and it seemed that Britain wanted to disengage itself from any problems relating to the far interior of South Africa, as well as being rid of further responsibilities in the area. Yet, within little more than a decade and half, the Orange Free State and the 'Zuid Afrikaansche Republiek' had both been subjugated in the course of the bloody South African War of 1899–1902!

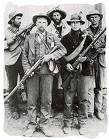

Towards the end of 1880, despite the failure of the Boer delegation led by Paul Kruger, requesting freedom for the Transvaal, the province had proclaimed its independence as a republic, but the discovery of gold on the Witwatersrand in the Transvaal in 1886 sealed the doom of the hardy pioneer folk. Gold and diamonds drew foreigners (‘uitlanders’ or ‘outlanders’) like a magnet. British imperial interest in the Transvaal led to its annexation by Sir Theophilus Shepstone, despite the Transvaal’s formal declaration of independence from the United Kingdom, and thus the first Boer War began on 16 December 1880. It led to the action at Bronkhorstspruit on 20 December 1880 – where the Boers, led by Francois Joubert, vanquished a British Army convoy. Despite the presence of British garrisons in the major Transvaal towns, the Boers were able to defeat a British column under Lt Col Anstruther at Bronkhorstspruit.

In the words of President Paul Kruger: “Let us linger for a moment on only one fight in this war, the Battle of Bronkhorstspruit , and that for certain reasons. This was an engagement with the 94th Regiment, which was on its way from Lydenburg to Pretoria. The Boer commanders, who had received news of its approach, sent Commandant Francois (Frans) Joubert with about 150 men, to meet it. When the two forces came within sight of each other, Joubert sent message to the British Commander, Colonel Anstruther, asking him to return to Lydenburg, in which case no fighting need take place. The man who carried the message was a burgher, called Paul de Beer, who spoke English well.

“Anstruther’s answer was brief:

“ ‘I am on my way to Pretoria and I am going to Pretoria!’ Joubert and his men, therefore, had no choice but to attack the English.

"The field of battle was a bare hill, on which stood a few hawthorn-trees. The English took up their position in a sunken road, while the burghers had to charge across open ground. The fight lasted only a few minutes, leaving about 230 of the English dead or wounded; the rest surrendered. Colonel Anstruther, who himself was mortally wounded, sent for Commandant Joubert, told him that he, Anstruther, had been beaten in fair fight, and asked him to accept his sword as a gift. He died a few minutes later.”

Further details, contained in an ancient book found above a barn in France, and which I’ve since translated from the French, confirm that the dying British general, Anstruther, had his sword presented to Joubert, as befitting ‘an officer and a gentleman’. It is said to be buried with Frans Held, in his grave - which I have never been able to visit. In terms of the Group Areas Act, the land was rezoned as a 'black area' long ago, and, during the turbulent times before I left South Africa, was considered unsafe.

Francois Joubert was my great-grandfather. 'Frans Held' to the Afrikaners; 'Frank Hero' to the British.

Monday, November 24, 2008

2nd BOER WAR ATROCITIES

The British take over.

SCORCHED EARTH AND CONCENTRATION CAMPS

THE FIRST HOLOCAUST OF THE 20TH CENTURY

THE DEATH OF FRANS HELD’S WIFE, MY GREAT-GRANDMOTHER

Just to recap:

By the time Britain acquired the strategically situated Cape of Good Hope from the Dutch in 1815, during the Napoleonic Wars, even the vernacular had evolved and changed ,and the French had become absorbed in the Dutch community. When their curé had been replaced by a Dutch dominie (pastor) they were highly incensed, and even more so when the schoolmaster was ordered to instruct his pupils in a foreign language which they could hardly understand, but by the time the British came, even the Dutch were not speaking the same language any more. A newly arrived official from Holland, who described their conversation as “Kaaps-Hollands¨ – Cape Dutch - had been heard to complain to a colleague that he could barely understand what the Dutch colonists were saying! From this Cape Dutch evolved what is today known as “Afrikaans.”

Many of these colonists were further united in their dissatisfaction with the new British government, and soon there were successive waves of migrations of Boer farmers (known as Trekboers), first to the east, along the coast away from the Cape towards what is came to known as Natal, and thereafter north towards the interior, eventually establishing the republics that came to be known as Orange Free State and the Transvaal (literally “across/beyond the Vaal River,” a tributary of the Orange River).

An important detail that should not be overlooked, is the fact that there were two Boer wars, and the vicinity of a small town by the name of Bronkhorstspruit was the scene of the opening battle of the first. This was where Francois Gerhardus Joubert distinguished himself in a feat of arms which gained him the nickname of “Frans Held” (Frank Hero). He had been prominent in public affairs before that; a signatory to the Sand River Convention on January 17,1852, at which the United Kingdom had entered into a treaty with approximately 5,000 Boer families, recognizing their independence in the territory north of the Vaal River. Thus the Zuid Afrikaansche Republiek (South African Republic ) had come into being.. In due course Frans Joubert was elected to the Transvaal Volksraad, or parliament .

Empress Eugénie of France suffers a loss

It would not be many years, however, before the status quo in the new ZAR and that of its neighbours to the south - the "Transorangians" of the Orange Free State – would be threatened because of the British government’s desire to expand the British Empire by forming a confederation of all the British colonies, independent Boer republics and independent African groups in South Africa under British control. By 1876 The 4th Earl of Carnarvon had realized that he would not be able to achieve his goal peacefully. “By acting at once,” he was to tell the then Prime Minister, Disraeli, “We may ... acquire ... the whole Transvaal Republic after which the Orange Free State will follow.” That he was prepared to use force to make the confederation a reality was proved by the Anglo-Zulu War in 1879, during which the son of Empress Eugénie, consort of Emperor Napoleon III of France, would be killed.

The Battle of Bronkhorstspruit

On December 20, 1880, a division of the British 94th Regiment, consisting of 9 officers and 354 other ranks under the command of Lt. Col P.R. Anstruther, on its way from Lydenburg to Pretoria were attacked by Comdt Frans Joubert and 200 men. Joubert had been instructed to prevent Anstruther’s detachment from joining up with the main body of British troops in Pretoria, but Anstruther rejected a written request from Joubert to discontinue his advance. A brief battle – which lasted only ten minutes followed, and in this short time the British lost 56 dead and 91 wounded, including their commander, who died later. The Boer losses were only 2 dead and 5 wounded. Today a plaque marks the site of the battlefield.

Discovery of gold re-awakens Britain’s interest in the Transvaal

I believe that information contained in a letter which “Frans Held” wrote to the Transvaal President should have been taken more seriously. Informing him that a hunting party which included a German with a knowledge of minerals, had discovered a rich gold reef near Vliegepoort, it also provided particulars about which that Government should take immediate steps, and was without a doubt a warning that should be connected more definitely with the re-awakening of Britain’s interest in the Transvaal. - But could any of the ensuing misery have prevented?

Scorched Earth and Internment Camps

By mid 1900, the Second Anglo-Boer War had been raging for well over a year, the overwhelming British force had occupied all the major towns and centres of the Boer Republics of the Orange Free State and the Transvaal, and the Boers had been forced to resort to hit and run guerrilla tactics in the open veld; but somehow they continued to inflict defeats upon the British in this way - to an extent that that eventually the war was to cost the British government a fortune by 1901 standards. The British became so exasperated with the military situation and the manner in which the Boers seemed to be able operate with impunity in the veld, that a new course of action was devised. In the last months of 1900, they began to build what eventually became 45 separate concentration camps, established for the purpose of systematically removing women and children from their farms to prevent them aiding and supplying the Boer soldiers ("burgers") in the field.

This rounding up of thousands of women and children was justified in a memorandum issued by a ruthless British commander, General Kitchener, at his headquarters in Pretoria, on 21 December 1900, by an explanation that it was to “protect them from the Blacks” and the relevant quotes are to be found in the Penguin Book "To the Bitter End: A Photographic History of the Boer War 1899 - 1902, Emanuel Lee."

The carnage begins

So it was that the British started not only rounding up as many Boer women and children as they could, but also destroying the farms, their only source of survival. The evacuation of the farms was accompanied by the burning and dynamiting of all farmhouses and buildings. Poultry, sheep and cattle were slaughtered, the houses looted and all fruit trees, grain or other crops burned down. This is not to say that all the British undertook this task with relish: many ordinary British soldiers were themselves appalled at what they were ordered to do. In the book, (LW Phillips,” With Rimmington", Edward Arnold, London, 1902) the reader is provided with a revealing insight into how the farms were cleared , provided by a soldier who took part in such an operation:

". . . Only the women are left. Of these, there are often three or four generations: grandmother, mother and family of girls. The boys over thirteen or fourteen are usually fighting with their papas. The people are disconcertingly like the English, especially the girls and the children - fair and big and healthy looking. These folk we invite out into the veldt or into the little garden in the front, where they huddle together in their cotton frocks and big sunbonnets, while our men set fire to the house . . . Sometimes they entreat that it may be spared, and once or twice in an agony of rage they have invoked curses on our heads. But this is quite the exception, as a rule they make no sign, and simply look on and say nothing. One young woman at the farm yesterday . . . went into a fit of hysterics when she saw the flames breaking out, and finally fainted away.”

He goes on to state that he wished he had his camera with him for “the farms would make a good subject,” explaining that they were “dry and burn well”, and describing the manner in which fire “burst out of windows and doors with a loud roaring,” while the women huddled together, comforting each other or holding their faces in each other’s laps

Books conjure up images that are enough to give the hardiest reader nightmares. If the fact that Queen Elizabeth has made a formal apology to the people of South Africa in 1999, for the atrocities of the Boer war, has not been enough to set at rest the doubts of any sceptics who might read this, eyewitness accounts, provided not only by Boers, but also by appalled British people, are numerous, and harrowing; most compelling among them the writings of an indomitable Cornish humanitarian and welfare worker by the name of Emily Hobhouse, and two other women, a Mrs Badenhorst and a Mrs Botha, in whom Emily found friends and allies. In her book, which is a veritable a mine of information, Emily Hobhouse would write: “It was late in the summer of 1900, that I first learnt of the hundreds of Boer women who became impoverished and were left ragged by our military operations … the poor women who were being driven from pillar to post, needed protection and organized assistance."

(I was overwhelmed with excitement when I discovered that the Hobhouse books are now obtainable online at Amazon. A book written by the Afrikaans woman, Alida Badenhorst under the pseudonym of “Tant Alie of Transvaal” and her “Diary 1880-1902" translated by Hobhouse, is also available. The descriptions in the “diary” conjure up images that are enough to give the most hardened reader nightmares.

Tant Alie’s account

From the victims” point of view, the removals from their homes to the camps were bewildering and terrifying. This extract from the diary of Alie Badenhorst, translated by Emily Hobhouse, reveals the panic and fear which accompanied these removals:

"I packed, and took bedding and tried to pack that also, but I was so crushed I did not know what I was doing, and they (the British) kept saying “quick, quick” so I gathered a few necessities together and thus was I driven forth from my home.”

The most harrowing:

“The winter of 1901 was particularly severe: even British troops in the field froze to death. In the camps, the damp and cold conditions played havoc amongst the tents: sickness began to spread amongst the children, and soon reached the adults. The death toll began to mount dramatically: the camp at Brandfort had the highest death rate during the worst months. "Worst of all,” she goes on to say, “because of the poor food, and having only one kind of food without vegetables, there came a sort of scurvy amongst our people. They got a sore mouth, and a dreadful smell with it; in some cases the palate fell out and the teeth, and some of the children were full of holes or sores in the mouth.”

(Alida Badenhorst, translated E. Hobhouse, "Tant Alie of Transvaal: Her Diary 1880-1902", George Allen and Unwin, London, 1923).

Unfortunatelty copyright regulations preclude me from quoting as liberally as I would like to do, but her description of how she went to the hospital one day and saw a child of nine “wrestling alone with death”, cannot be left out of this story. Inquiring as to where she might find the child’s mother, she learnt that the mother had died a week before, the father was prisoner of war in Ceylon, and the little girl’s sister had died that very morning. “I pitied the poor little sufferer as I looked upon her, “Tant Alie” writes. “ . . . There was not even a tear in my own eyes, for weep I could no more. I stood beside her and watched until a stupefying grief overwhelmed my soul . . . O God, be merciful and wipe us not from the face of the earth." (Also quoted from: Alida Badenhorst, translated E. Hobhouse, George Allen and Unwin, London, 1923).

Emily Hobhouse the translator

The Cornish humanitarian and welfare worker, proclaimed an “honorary South African”.

Driven to help the women and children in the camps, she somehow obtained permission from the British government to start a non-political, non-sectarian “South African Women and Children’s Distress fund”, pleading on behalf of “those deprived of hearth and home by the war, be they Boer or British”, and it was only after an appeal for monetary subscriptions proved successful, that she announced her intention to go to South Africa. When she left England, she only knew about one camp, the one at Port Elizabeth, but on arrival in Cape Town she soon learned of others in several places.

South Africa was a country totally unknown to her, she could not speak a word of Afrikaans. In addition, in order to be permitted to do what she dreamt of doing, she needed the approval of the formidable Lord Kitchener; but hers was a mission of love and compassion, and although bitterly disappointed when he would only grant her permission to proceed as far as a place called Bloemfontein, she set off, arriving there on the 24th of January 1901, “dumped down” as she puts it, “on the southern slope of a kopje (small hill) right out on the bare brown veld!” It is fortunate for posterity that, looking in the maze of tents, she tracked down a Mrs Philip Botha, whose sister she had met in Cape Town, and others who told her their stories. What she relates is right up there with Alida Badenhorst’s records; among some of the most moving of all accounts of the awful suffering that the Boer women were forced to endure in the concentration camps.

To Emily Hobhouse we owe many of the grim details of what it meant to be a child in a concentration camp, and she paid the price for this once she returned to her homeland. Among others, she has told the story of the young Lizzie van Zyl who died in the Bloemfontein camp: “She was a frail, weak little child in desperate need of good care. Yet, because her mother was one of the “undesirables” due to the fact that her father neither surrendered nor betrayed his people, Lizzie was placed on the lowest rations and so debilitated by hunger that, after a month in the camp, she was transferred to the new small hospital. Here she was treated harshly. The English disposed doctor and his nurses did not understand her language and, as she could not speak English, labelled her an idiot although she was mentally fit and normal. One day she dejectedly started calling: 'Mother! Mother! I want to go to my mother!'

“Mrs Botha, walked over to her to console her. She was just telling the child that she would soon see her mother again, when she was brusquely interrupted by one of the nurses who told her not to interfere with the child as she was a nuisance.” Shortly afterwards, Lizzie van Zyl died.

The cost of “interference”

In later years she was to write: “We in England are still dunces in the great world-school; our leaders are still struggling with the unlearned lesson that liberty is the equal right and heritage of every child of man, without the distinction of race, colour or sex!”

That her own nation misinterpreted her actions and motives during the Anglo-Boer War remained a bitter pill to her up to the end of her life. On 1 May 1926 she would write:

“Truth for ever on the scaffold. Wrong for ever on the throne!”

Her work in the concentration camps in South Africa had made “almost all my people look down upon me with scorn and derision. The press abused me, branded me a rebel, a liar, an enemy of my people, called me hysterical and even worse.” One or two newspapers, for example the Manchester Guardian, tried to defend her, but, she continues, “it was an unequal struggle with the result that the mass of the people was brought under an impression about me that was entirely false. I was ostracized. When my name was mentioned, people turned their backs on me. This has now continued for many years and I have had to forfeit many a friend of my youth.”

Tibbie Steyn

The love and esteem bestowed on her by the South African nation remained what she called, “a sweet drop in her cup of bitterness” to the end of her life. Without her knowledge, and on the initiative of Mrs. Steyn, wife of the president of the Orange Free State, a sum of £2,300 was collected for her by means of “half-a-crown” collection lists in 1921. This money was sent to her with the explicit mandate that she had to buy a small house for herself somewhere along the coast of Cornwall, where she longed to be. As her financial position was such that she had to forego essential amenities, she could not, with the means at her disposal, have considered purchasing a house.

In May 1921, she wrote to Tibbie:

“I find it impossible to give expression to the feelings that overpowered me when I heard of the surprise you had prepared for me. My first impulse was not to accept any gift, or otherwise to devote it to some or other public end. But after having read and re-read your letter, I have decided to accept your gift in the same simple and loving spirit in which it was sent to me.” She purchased a house at St. Ives in Cornwall, from where she wrote many a letter in which she expressed her gratitude and appreciation.

Mrs. Steyn always arranged to send to Emily, on her birthday, a consignment of Orange Free State canned fruit, preserves, biltong (dried meat) and other delicacies. This gift was a great source of pleasure to her and she was very proud of it. It is said that she seldom received a guest who was not persuaded to taste some of the South African fare.

Meanwhile her bodily strength was gradually ebbing. She had realized months before the time that her end could not be far off, and often yearned for it passionately. Although her last letters continued to bear proof of her interest in mankind and in human affairs, they nevertheless bore unmistakable evidence of the fact that she was preparing for her departure to the next world. Before that letter reached South Africa, she died of pleurisy, cardiac degeneration and some internal form of cancer. There was a burial service in London, but her ashes found a final resting place in a niche at the Women’s Memorial in Bloemfontein, South Africa, on 26 October 1926.

Women’s Memorial - The “Vrouemonument”

In 1906, a project was initiated by Tibia’s husband, the then ex-president Steyn of the Orange Free State, “in commemoration of the sufferings of the Boer women” and in 1913 the Women’s Memorial, was dedicated in Bloemfontein “ to the women and children who had died during the war.” As a close associate of Steyn and his wife, Emily - who had been instrumental in helping to finalise the design of the monument - was to have presented an opening address. Unfortunately, because of ill health she could not attend, but her address was read at the opening, and subsequently published. In it she outlined a significant anomaly: “I think, for the first time, a woman is chosen to make the commemorative speech over the National dead - not soldiers - but women - who gave their lives for their country”. (Van Reenen, 1984:402) How remarkable that it was an English woman commemorating the Afrikaner national dead!

The only other woman interred at the monument is Rachel (Tibie) Steyn, the wife of the president, who was honoured in this way. She was one of my mother’s dearest friends.

Footnote:

On May 25, 1901, in Springfontein, Emily Hobhouse had seen a young woman sitting on a tiny coffin. She held a very sick child (her only one) on her lap. At her feet another woman sat weeping. Behind her stood a woman, crying out to the Lord to “look upon” the tragedy. The woman with the little child was not crying or looking at the child on he lap. She could only stare fixedly before her; her face ashen. This image was deeply engraved in Emily’s heart. She had sent for a doctor who was about a mile away, but he replied that he was only responsible for those in his own camp.

It was Emily who, when Pres Steyn conceived the idea of a monument to the women and children who had been in the camps, sketched the image she carried in heart, for the designer of the statue - Frans Soff. It was then brought into being by South Africa’s acclaimed sculptor, Anton van Wouw. An inscription reads, “What is before me is only an image of true love, faithfulness and courage; namely the Afrikaner woman. It is signed: M.T. Steyn.

World-travellers who have already seen the greatest and most impressive memorials elsewhere, constantly declare that no other has moved them like this one. One need only stand here before the group in this image, and see the commemorative needle reaching high up into the blue heavens, to have tears well up in one’s eyes.

Was Kitchener the main “perpetrator”, or was it actually Roberts?

Lord Kitchener is usually blamed for the scorched earth policy, but the architect of the atrocities was none other than Field Marshal Lord Roberts of Kandahar, V.C., K.G., K.P., G.C.B., O.M., G.C.S.I., and G.C.I.E.

Now that we have Canadian troops in Afghanistan, I try to rationalize his actions by thinking that perhaps it was his experiences there, that had sent him to South Africa prepared to win the battle by whatever diabolical means he saw fit to employ. Members of our Canadian forces, even if wounded, know that returning to Canada hopefully means returning to “home and family”. The Boer soldiers, on the other hand, had no homes and frequently no families left to return to, and all that had precipitated the horror in the first place, was the unfortunate fact that gold and diamonds had been discovered in their country!

Following the defeat of the conventional Boer forces, Kitchener succeeded Roberts as overall commander in November 1900, and after the failure of a reconciliatory peace treaty in February 1901 (due to British cabinet veto) which Kitchener had negotiated with the Boer leaders, Kitchener inherited and expanded the successful strategies devised by Roberts to crush the Boer guerrillas.

In a brutal campaign, these strategies – as we have already seen - removed civilian support from the Boers with a scorched earth policy of destroying Boer farms, slaughtering livestock, building blockhouses, and moving women, children and the elderly into concentration camps. Conditions in these camps, which had been conceived by Roberts as a form of controlling the families whose farms he had destroyed, began to degenerate rapidly as the large influx of Boers outstripped the minuscule ability of the British to cope. The camps lacked space, food, sanitation, medicine, and medical care, leading to rampant disease and a staggering 34.4% death rate for those Boers who were kept there. The biggest critic of the camps was a Cornish humanitarian and welfare worker EMILY HOBHOUSE. As chief of staff to Lord Frederick Roberts, Kitchener was responsible for developing Roberts’ strategies to deal with the Boer guerrilla campaign. His decision to destroy Boer farms and to move civilians into concentration camps resulted in his being highly criticized by politicians such as David Lloyd George and Charles Trevelyan.

Please note: Following the exaple set by my gentle, forgiving mother, I have written this solely to honour the women featured in the story, and with no vestige of malice or bitterness.

Sunday, November 9, 2008

Until I embarked on this enterprise I knew very little about the Boer War

1914

1933

By the time my sister was born, South Africa - like Canada, India and Australia - was a dominion of the British Empire. Our home language was English, we could speak Afrikaans, and whereas my sister and my father could communicate in Latin (which I envied them) I seem to think that my first language was actually Sesuto (SeSotho); particularly as I loved my Basotho nanny more than anyone else on earth, and, because my father was involved in public life, I saw more of Lizzie than I did of my parents. I also recall being the only white child in a black, farm school at one stage.

Until my mother, my sister, and I moved away from our idyllic little Free State town after my father’s death, my life had been as perfect as any child would wish; but, like many openhearted and generous men, he had — while being incapable of turning away anyone who needed help (including a financially strapped church in another town)— failed to make provision for his own his family. So it happened that, soon after arriving in the ‘Big’and more judgmental city of Bloemfontein, where my sister had found work, my blissful existence was seriously marred. It was there that one of my new schoolfellows turned her back on me with a scornful, “Get away from me, you dirty Dutchman!”

How I hated having a Dutch name, which might (horror of horrors!) have labelled me a "Boer" - especially as my father consorted with people like the Duke of Connaught, I had an aunt who had been presented at court, and, as a member of a Brownie pack, I had once proudly seen my father welcome Lord and Lady Clarendon on the steps of our Town Hall. Flags hung at half-mast and all places of business were closed on the day of my father's death.

How, I would wonder, could he possibly have run away, at the age of sixteen, from his prestigious English private school in Bloemfontein and contrived to find himself a horse in order to fight against the British, when we had a large portrait of him in the dining room, standing, shoulders squared, in his uniform as a major in the South African Forces during the Great War - on the side of the British? Truly one would have to understand the history of South Africa very well indeed, in order to be able to appreciate with what forgiving hearts its people had been blessed.

The Union of South Africa, another war and a rebellion.

On 31 May 1910, the two former Boer republics of the Transvaal and the Orange Free State, and the British colonies of Natal and the Cape, joined together to become the Union of South Africa under the British flag, but only four years later the brave new country faced a new crisis when Britain called upon its dominions to help in a fight against a new enemy in Europe - Germany. The Afrikaners in the newly-formed Union of South Africa were put in the spot, as they were reluctant to fight on the side of the British - their erstwhile foes - and the country was divided again when a rebellion was instigated. Finally, after that had been suppressed, South African entered the war on the British side, and the government having agreed to attack the German colony of South West Africa, that is where both my father and the man who became my father-law, saw service. Surprisingly, it was in a Canadian Military Journal published in 1985, that I recently found the most glowing account of South Africa’s illustrius record and contribution to the victories that brought that war to an end.

When peace was declared, Jan Christiaan Smuts of South Africa was among the architects of the ‘League Of Nations’, an association of countries established in 1919 by the Treaty of Versailles to promote international cooperation and achieve international peace and security! When it was replaced by the United Nations in 1945, it was Smuts who drafted the Covenant of the United Nations, which is considered to have been his major achievement; but it should also not be forgotten that as a Field Marshal of the Allied Forces during WW2, he enjoyed the respect and friendship of both General Eisenhower and the King of England.

Until the name was changed recently, the main airport in South Africa bore his name.

My father

For most of my life, and long after his own was over — for as long as there were people alive to attest to this amazing, gifted person, his integrity, character and life — to hear people unfailingly wax eloquent regarding his virtues, the moment his name was mentioned, has been a privilege enjoyed by few children. I was only six when he died, and now I, too, am old, but I retain the most vivid memories of him. Although, in my novel, ‘Tarnished Idols’ the romantic story itself is not true, I used him and his relationship with my sister and me, in my book. He really did speak Latin, and he really did teach himself to write shorthand, which is why, in his obituary, the Ficksburg News quoted one speaker as reflecting:

“As a bilingualist he was outstanding, and could not only write as well as speak most fluently in either medium, but was outstandingly able in his quick interpretation of speeches — a qualification that few could claim — with equal facility. (Obviously the shorthand was an asset!) “As a companion he was entertaining, and whatever the conditions, always cheerful and optimistic. As a host he was hospitality itself.

“As the deceased had seen active service and retired with the rank of Major on the reserve list, a firing party of Ficksburg School Cadets under command of Captain Pienaar was formed outside the church and presented arms to the coffin, which was still draped with the Union Flag. And the funeral cortège was preceded by the party at slow march with reversed arms. The interment arrangements were in the hands of the Mayor, Mr. A.A. Keyter jnr. and the bearers were the Ficksburg Town Councillors, and others: Messrs. N.J. Leonard, S.D.Barnett, I.Danneman, P.R van Niekerk, G. Leipoldt, Caved. Heever, J.J. le Roux, assistant Town Clerk, J.H. van Heerden, attorney of Theunissen, who had been the late Mr. van Zyl’s employer in earlier days. The chief mourners were the widow and her elder daughter, Miss Claudia van Zyl, accompanied by several of their closest friends.

“On arriving at the cemetery the firing party, with bowed heads, formed an avenue for the procession to pass through, and, after the final obsequies, ranged on either side of the grave and fired three volleys over the mortal remains, in the intervals of which the bugles sounded the retreat. (Sunset.) After the firing of the last volley they again presented arms and the bugles sounded the Last Post. ... At the end, Mr. Van Heerden thanked the public for their attendance and the many expressions of sympathy to the family.

“All sections of the community, civic, legal, commercial, and agricultural, of town and country were present, and all places of business in town, including the banks, were closed during the funeral, and as a mark of respect and recognition of the deceased’s military service, Colonel P. Krog and Lieutenant JEFF. Becker were in uniform. The sympathy of the Girl Guides and Brownies was demonstrated to Miss Claudia van Zyl, a Guide, and little Miss Marie van Zyl, a Brownie, by the uniformed presence of their officers, Miss Tenant, Captain, Mrs. Snelling, second Captain, and Miss Saayman, acting Brown Owl.

. . . .

Whatever could have motivated my father and his friend, Deneys Reitz to run away, at the age of sixteen, from their prestigious English private school in Bloemfontein and contrive to find themselves horses in order to fight against the British? - NOW I KNOW!

1933

By the time my sister was born, South Africa - like Canada, India and Australia - was a dominion of the British Empire. Our home language was English, we could speak Afrikaans, and whereas my sister and my father could communicate in Latin (which I envied them) I seem to think that my first language was actually Sesuto (SeSotho); particularly as I loved my Basotho nanny more than anyone else on earth, and, because my father was involved in public life, I saw more of Lizzie than I did of my parents. I also recall being the only white child in a black, farm school at one stage.

Until my mother, my sister, and I moved away from our idyllic little Free State town after my father’s death, my life had been as perfect as any child would wish; but, like many openhearted and generous men, he had — while being incapable of turning away anyone who needed help (including a financially strapped church in another town)— failed to make provision for his own his family. So it happened that, soon after arriving in the ‘Big’and more judgmental city of Bloemfontein, where my sister had found work, my blissful existence was seriously marred. It was there that one of my new schoolfellows turned her back on me with a scornful, “Get away from me, you dirty Dutchman!”

How I hated having a Dutch name, which might (horror of horrors!) have labelled me a "Boer" - especially as my father consorted with people like the Duke of Connaught, I had an aunt who had been presented at court, and, as a member of a Brownie pack, I had once proudly seen my father welcome Lord and Lady Clarendon on the steps of our Town Hall. Flags hung at half-mast and all places of business were closed on the day of my father's death.

How, I would wonder, could he possibly have run away, at the age of sixteen, from his prestigious English private school in Bloemfontein and contrived to find himself a horse in order to fight against the British, when we had a large portrait of him in the dining room, standing, shoulders squared, in his uniform as a major in the South African Forces during the Great War - on the side of the British? Truly one would have to understand the history of South Africa very well indeed, in order to be able to appreciate with what forgiving hearts its people had been blessed.

The Union of South Africa, another war and a rebellion.

On 31 May 1910, the two former Boer republics of the Transvaal and the Orange Free State, and the British colonies of Natal and the Cape, joined together to become the Union of South Africa under the British flag, but only four years later the brave new country faced a new crisis when Britain called upon its dominions to help in a fight against a new enemy in Europe - Germany. The Afrikaners in the newly-formed Union of South Africa were put in the spot, as they were reluctant to fight on the side of the British - their erstwhile foes - and the country was divided again when a rebellion was instigated. Finally, after that had been suppressed, South African entered the war on the British side, and the government having agreed to attack the German colony of South West Africa, that is where both my father and the man who became my father-law, saw service. Surprisingly, it was in a Canadian Military Journal published in 1985, that I recently found the most glowing account of South Africa’s illustrius record and contribution to the victories that brought that war to an end.

When peace was declared, Jan Christiaan Smuts of South Africa was among the architects of the ‘League Of Nations’, an association of countries established in 1919 by the Treaty of Versailles to promote international cooperation and achieve international peace and security! When it was replaced by the United Nations in 1945, it was Smuts who drafted the Covenant of the United Nations, which is considered to have been his major achievement; but it should also not be forgotten that as a Field Marshal of the Allied Forces during WW2, he enjoyed the respect and friendship of both General Eisenhower and the King of England.

Until the name was changed recently, the main airport in South Africa bore his name.

My father

For most of my life, and long after his own was over — for as long as there were people alive to attest to this amazing, gifted person, his integrity, character and life — to hear people unfailingly wax eloquent regarding his virtues, the moment his name was mentioned, has been a privilege enjoyed by few children. I was only six when he died, and now I, too, am old, but I retain the most vivid memories of him. Although, in my novel, ‘Tarnished Idols’ the romantic story itself is not true, I used him and his relationship with my sister and me, in my book. He really did speak Latin, and he really did teach himself to write shorthand, which is why, in his obituary, the Ficksburg News quoted one speaker as reflecting:

“As a bilingualist he was outstanding, and could not only write as well as speak most fluently in either medium, but was outstandingly able in his quick interpretation of speeches — a qualification that few could claim — with equal facility. (Obviously the shorthand was an asset!) “As a companion he was entertaining, and whatever the conditions, always cheerful and optimistic. As a host he was hospitality itself.

“As the deceased had seen active service and retired with the rank of Major on the reserve list, a firing party of Ficksburg School Cadets under command of Captain Pienaar was formed outside the church and presented arms to the coffin, which was still draped with the Union Flag. And the funeral cortège was preceded by the party at slow march with reversed arms. The interment arrangements were in the hands of the Mayor, Mr. A.A. Keyter jnr. and the bearers were the Ficksburg Town Councillors, and others: Messrs. N.J. Leonard, S.D.Barnett, I.Danneman, P.R van Niekerk, G. Leipoldt, Caved. Heever, J.J. le Roux, assistant Town Clerk, J.H. van Heerden, attorney of Theunissen, who had been the late Mr. van Zyl’s employer in earlier days. The chief mourners were the widow and her elder daughter, Miss Claudia van Zyl, accompanied by several of their closest friends.

“On arriving at the cemetery the firing party, with bowed heads, formed an avenue for the procession to pass through, and, after the final obsequies, ranged on either side of the grave and fired three volleys over the mortal remains, in the intervals of which the bugles sounded the retreat. (Sunset.) After the firing of the last volley they again presented arms and the bugles sounded the Last Post. ... At the end, Mr. Van Heerden thanked the public for their attendance and the many expressions of sympathy to the family.

“All sections of the community, civic, legal, commercial, and agricultural, of town and country were present, and all places of business in town, including the banks, were closed during the funeral, and as a mark of respect and recognition of the deceased’s military service, Colonel P. Krog and Lieutenant JEFF. Becker were in uniform. The sympathy of the Girl Guides and Brownies was demonstrated to Miss Claudia van Zyl, a Guide, and little Miss Marie van Zyl, a Brownie, by the uniformed presence of their officers, Miss Tenant, Captain, Mrs. Snelling, second Captain, and Miss Saayman, acting Brown Owl.

. . . .

Whatever could have motivated my father and his friend, Deneys Reitz to run away, at the age of sixteen, from their prestigious English private school in Bloemfontein and contrive to find themselves horses in order to fight against the British? - NOW I KNOW!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

.jpg)

.jpg)